Keeping it Objective.

For clinicians and some die hard foot geeks, we often like to keep things objective. What could be more objective than an angular measurement? A few important measurements when examining or radiographing feet can give us information about clinical decision making (not that we suggest radiographs for mensuration purposes unless you are a surgeon, but when they are already available, why not put them to good use ?). When things fall outside the accepted range, or appear to be heading that way, these numbers can help guide us when to intervene.

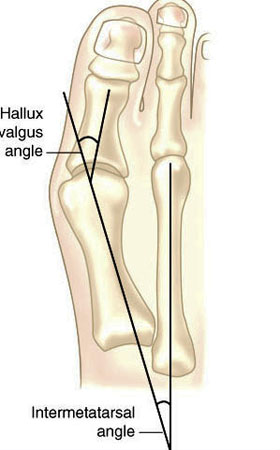

Hallux valgus refers to the big toe headed west (or east, depending on the foot and your GPS). In other words, the proximal and distal phalanyx of the great toe (hallux) have an angle with the 1st metatarsal shaft of typically > 15 degrees. This angle, called the Hallux Valgus Angle (HVA above) is used to judge severity, often for surgical intervention purposes but can guide conservative management as well.

Metatarsus Primus Varus (literally, varus deformity of the 1st metatarsal) often accompanies Hallux Valgus. It describes medial deviation of the 1st metatarsal shaft, greater than 9 degrees. This angle is called the intermetatarsal angle and is measured by the angle formed by lines drawn parallel along the long axis of the 1st and 2nd metatarsal shafts.

One other measurement is the Distal Metatarsal Articular Angle, which measures the angle between the metatarsal shaft and the base of the distal articular cap (ie, where the cartilage is) of the 1st metatarsal. This typically should be less than 10 degrees, preferably less than 6 degrees. Remember, these are static angles, things can change with movement, engagement, weight bearing strategies and shoes. What you see statically does not always predict dynamic angles and joint relationship.s

Are you doing surgery? Perhaps, as a last resort. Hallux valgus and metatarsus primus varus can be treated conservatively.

How do you do that?

The answer is both simple and complex.

The simple answer is: anchor the head of the 1st ray and normalize foot function. This could be accomplished by:

- EHB exercises to descend the head of the 1st metatarsal

- exercise the peroneus longus, to assist in descending the head of the 1st metatarsal

- short flexor exercises, such as toe waving, to raise the heads of the lesser metatarsals relative to the 1st

- work the long extensors, particularly of the lesser metatarsals to create balance between the flexors and extensors

- consider using a product like “Correct Toes” to normalize the pull of the muscles and physically move the proximal and distal phalanyx of the hallux

- wear shoes with wide toe boxes, to allow the foot to physically splay

- consider using an orthotic with a 1st ray cut out, to help descend the head of the 1st metatarsal

This is by no means an exhaustive list and you probably have some ideas of your own.

The complex answer is that in the above example, we have only included conservative interventions for the foot and have not moved further up the kinetic (or neurological chain). Could improving ankle rocker help create more normal mechanics? Would you accomplish this by working the anterior leg muscles, the hip extensors, or both? Could a weak abdominal external oblique be contributing? How about a faulty activation pattern of the gluteus medius? Could a congenital defect or genetic be playing a role? We have not asked “What caused this to occur in the 1st place?”

Examine your patients and clients. Understand the biomechanics of what is happening. Design a rehab program based on your findings. Try new ideas and therapies. it is only through our failures that we can truly learn.

The Gait Guys

references used:

http://www.bjjprocs.boneandjoint.org.uk/content/90-B/SUPP_II/228.3

http://www.slideshare.net/ANALISIS/hallux-valgus-2008-pp-tshare

http://www.orthobullets.com/foot-and-ankle/7008/hallux-valgus

http://www.slideshare.net/bahetisidharth/hallux-valgus-31768699?related=1